The 30% Drop: How Delayed Eating Kills Performance (Even If You Hit Your Macros)

A new study reveals a paradox: athletes with full muscle glycogen stores still suffered a 30% performance drop. Here is why nutrient timing matters more than we thought.

For years, I treated the "anabolic window" like a ticking time bomb.

You know the drill. You finish a hard ride, and the clock starts. You have 30, maybe 45 minutes to get protein and carbs into your system, or else the workout was wasted, your muscles will wither, and you’ll never recover. I’ve definitely chugged a recovery shake in the shower because I was terrified of hitting minute 61.

Over the last decade, sports science has largely relaxed on this. The consensus shifted: Don't panic. As long as your total daily calories and macronutrients are sufficient, the timing doesn't matter as much as we thought. Your muscles will eventually refill their fuel tanks (glycogen) over 24 hours.

I was comfortable with this new, relaxed reality. But a recent study I came across has completely broken my brain—and forced me to rethink how I eat after a ride.

It turns out, your muscles can be fully fueled, and you can still perform terribly.

The Experiment

The setup of the study was elegant and brutal. Researchers took a group of active men and put them through a two-day wringer.

Day 1: They did high-intensity intervals (10 x 2 minutes at roughly 95% of peak power). A hard session, but manageable.

The Intervention: This is where it gets interesting. Everyone ate the exact same amount of carbohydrates and calories over the 24-hour period. But the timing was different.

- Group A (Immediate): Consumed carbohydrates immediately after the workout and at regular intervals for the next few hours.

- Group B (Delayed): Consumed zero-calorie placebos for hours post-workout, then crammed all those missing carbs in later in the day.

Day 2: The participants came back to the lab for a "death test." They repeated the 2-minute intervals from the day before, but this time, there was no limit. They were told to go until failure—As Many Reps As Possible (AMRAP).

If you follow the "total daily energy matters most" logic, both groups should have performed roughly the same. They both ate the same food, just at different times.

The Result: The "Immediate" eaters churned out an average of 18 intervals. The "Delayed" eaters managed only 12 or 13 intervals.

That is a 30% drop in performance. In the world of endurance sports, 30% isn't a marginal gain; it’s a different zip code.

The Mystery of the Full Tank

Here is the twist that keeps me up at night. The researchers didn't just measure performance; they took muscle biopsies.

They punched holes in the participants' legs right before the Day 2 test to measure muscle glycogen levels. Logic dictates that the "Delayed" group bonked early because their tanks were empty, right?

Wrong.

The biopsies showed no significant difference in muscle glycogen between the two groups. Both groups had replenished their muscle fuel stores to near-baseline levels.

Let that sink in. The "Delayed" group had just as much fuel in their legs as the "Immediate" group. Their engines were primed. Their tanks were full. But when they hit the gas, the car wouldn't go.

If It’s Not Fuel, What Is It?

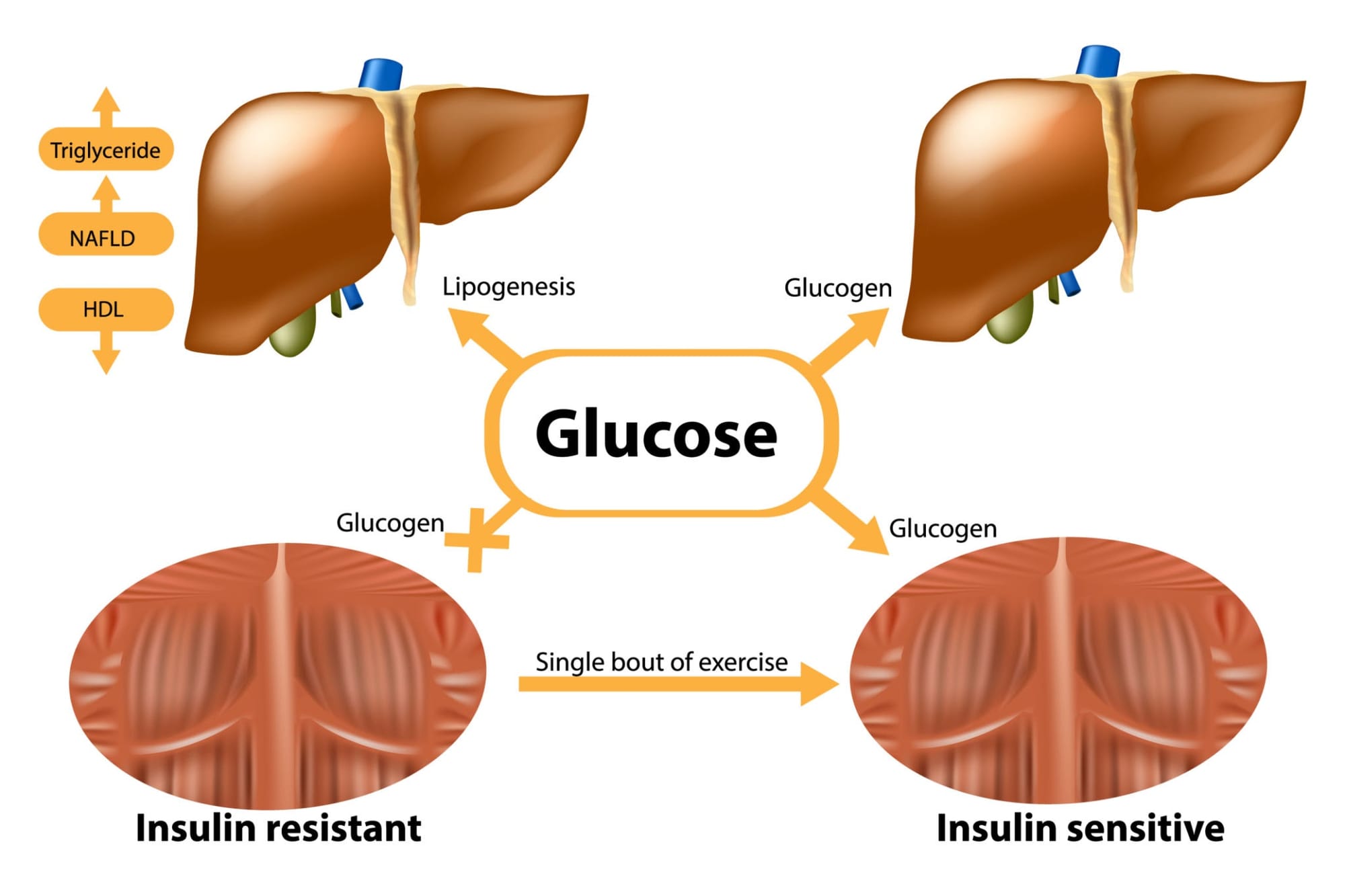

This finding disrupts the simple "carbs in = watts out" equation. If the muscle glycogen was there, why couldn't they access it?

There are a few theories, and they suggest that our bodies are smarter (and pettier) than we give them credit for.

1. The Liver is the Governor While muscle glycogen was restored, we don't know about liver glycogen. The liver is the brain's fuel gauge. If the liver senses a deficit—because you spent four hours fasting after a hard workout—it might signal the brain to throttle your physical output to protect the brain's glucose supply. The tank in the legs is full, but the central computer is in "Safe Mode."

2. Within-Day Energy Deficit We tend to look at calories on a 24-hour scale. But the body lives minute to minute. Even if you "make up" the calories at dinner, delaying food after a morning workout means your body spent 6 to 8 hours in a severe caloric deficit.

During that time, your body isn't just waiting patiently; it's ramping up stress hormones like cortisol and potentially downregulating metabolic processes. You can pay back the caloric debt, but you can't undo the stress response of the debt itself.

The Practical Takeaway

Does this mean we need to go back to panic-eating in the shower?

If you are riding once a week: Probably not. If you have 48+ hours between hard sessions, the timing becomes less critical. Your body has plenty of time to stabilize.

If you are training back-to-back: This is the game-changer. If you are doing "doubles" (morning and evening), stage racing, or just hitting hard sessions on Saturday and Sunday, immediate fueling is non-negotiable.

You cannot trick your body by backloading calories. You might refill the muscle, but you won't recover the performance.

My takeaway is this: The "Glycogen Window" isn't about refilling the tank; it's about convincing your body that it’s safe to spend energy again. It’s a safety signal.

So, when I get off the bike now, I eat. Not because I’m terrified of losing gains, but because I want my body to know that the war is over, the famine is cancelled, and we can get ready to fight again tomorrow.