The FTP Trap: Why Your Numbers Stop Moving (And Why That’s Okay)

Frustrated by a stagnant FTP? Here is the physiological timeline of threshold adaptation, from lactate buffering to the inevitable plateau, and how to train smarter.

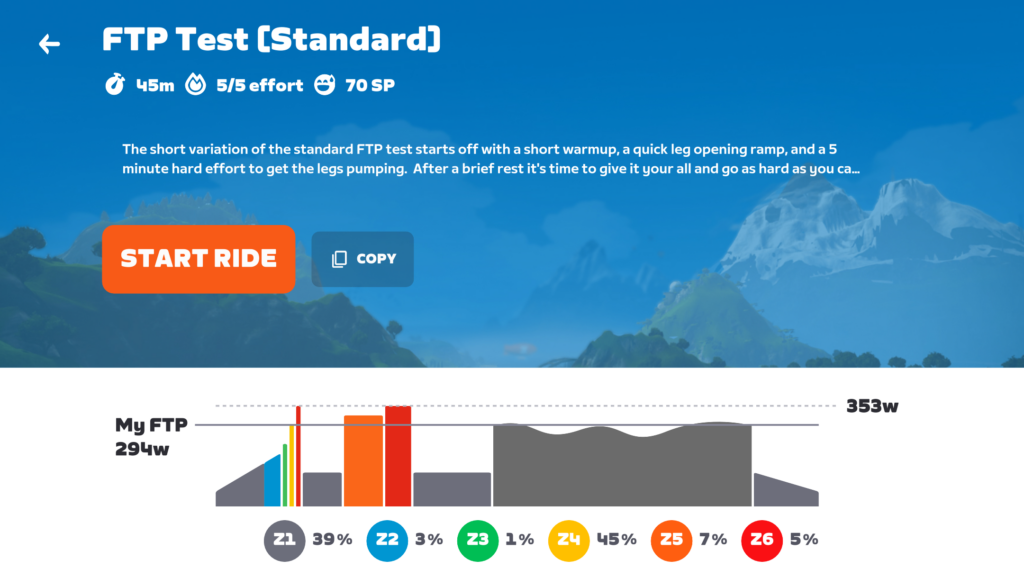

In the world of cycling, Functional Threshold Power (FTP) is the vanity metric to end all vanity metrics. It is the number we put in our Instagram bios, the figure we casually drop on group rides, and the stick we use to beat ourselves up when we feel slow.

I have spent years chasing that number. I’ve treated it like a high score in a video game, assuming that if I just grind harder, the number goes up linearly forever.

But biology is not a video game.

Recently, I’ve been diving deep into the physiological mechanics of threshold training—what is actually happening under the hood when we spend 20 minutes suffering at the limit. What I found changed how I view those painful intervals. It turns out, FTP isn’t a definition of your worth as a cyclist; it’s just a metabolic marker. And understanding how that marker moves (and when it stops) is the difference between getting faster and getting burned out.

Here is my take on the timeline of adaptation, and why you are likely staring at a plateau right now.

The Law of Diminishing Returns

If you are new to structured training, or you’re coming back after a long hiatus (perhaps due to injury or just life getting in the way), you are in the "golden window." In the first year or two of serious riding, FTP skyrockets. You look at the bike, and you get faster.

But for those of us with "training maturity"—meaning we’ve been riding consistently for a few years—the game changes. We enter the phase of diminishing returns. We have to work twice as hard for half the gains.

This is the emotional trap. We expect the same rate of progress we saw three years ago, and when it doesn’t happen, we panic. We add more volume. We smash ourselves. But the reality is, once you are fit, FTP becomes a game of marginal gains (fighting for 3-5% improvements) and minimizing losses.

Phase 1: The "Control" Phase (Weeks 1-4)

Let’s say you start a new block of threshold intervals today. What happens in the first month?

Physiologically, you aren't building massive new muscles yet. You are optimizing your body’s waste management system.

When you ride at threshold, you are producing energy via glycolysis. The byproduct isn't just lactate; it's hydrogen ions. These ions cause muscle acidity—that burning sensation in your quads. The first adaptation your body makes is improving its ability to buffer and clear this acidity.

But there is a psychological adaptation happening here, too. I call it The Muting of the Alarm.

Your body is designed to survive. When acidity rises, your nervous system rings a loud alarm bell that screams, "Stop! You are dying!" This is the suffering. In the first few weeks of training, you aren't necessarily getting stronger; you are just teaching your brain that this alarm is a false positive. You are learning to tolerate the noise.

The Metric to Watch: Ignore the watts for a second. Look for "Control." In Week 1, a 10-minute threshold effort feels ragged and desperate. By Week 3, that same wattage feels smooth. You aren't surging; you’re holding it steady. That sense of control is the first sign the training is working.

Phase 2: The Structural Shift (Weeks 4-8)

Once you’ve established control, the deeper physiological changes kick in. This is where the magic happens.

During this phase, we see improvements in glycogen storage and enzymatic activity. We effectively turn into hybrid vehicles. We get better at using the lactate produced by our fast-twitch fibers as fuel for our slow-twitch fibers.

Research Note: This process involves proteins called MCT1 and MCT4 transporters. MCT4 shuttles lactate out of the high-intensity muscle fibers, and MCT1 shuttles it into the oxidative fibers to be recycled as energy. This "Lactate Shuttle" is what separates the good riders from the great ones.

The Strategy: This is where many of us mess up. We think we need to push the power higher. Instead, we should be pushing the duration longer. If you can hold 300 watts for 10 minutes, don't try to hold 320 watts next week. Try to hold 300 watts for 15 minutes. Extend the time in zone (TIZ). That is how you build a diesel engine.

The Stagnation Point (Weeks 8-12)

Here is the hard truth I’ve had to learn: You cannot build FTP forever.

Usually, around the 8 to 10-week mark of a dedicated threshold block, you will hit a ceiling. The gains stop. You might see a higher heart rate for the same power, or your RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) stays high even on good days.

This is the danger zone. When the gains stop, our instinct is to push harder. But that usually leads to non-functional overreaching (burnout). When the subjective feeling (it hurts a lot) and the objective data (the power isn't going up) align to say "we're stuck," it’s time to change the stimulus. Move on to VO2 max work, or go back to base.

Practical Takeaways for the Time-Crunched

As a dad with a full-time job, I don't have 15 hours a week to train. If you are in the same boat, here is how to apply this:

- Don't Obsess Over the Number: You are not your FTP. It’s just a metric of metabolic fitness.

- Interval Length Matters: Stop doing 4-minute "threshold" intervals. That’s not enough time to stress the aerobic system. Aim for a minimum of 10 minutes per interval. Work your way up to 20 or even 30-minute blocks.

- Frequency: You don't need to do this every day. Twice a week is plenty.

- The "Hard Start": If you are short on time, try "hard start" intervals. Go out at 110% of FTP for the first minute to spike your lactate and heart rate, then settle into threshold. It forces your body to process that lactate immediately, giving you a higher training stimulus in less time.

Cycling is a long game. The goal isn't to have the highest FTP in January; it's to be a consistent, durable athlete year-round. Sometimes that means accepting the plateau and simply enjoying the ride.